For the first time since its creation in 1946, the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) — a global intergovernmental body dedicated to the promotion of gender equality — focused its annual session on digital technologies. Every year, this two-week gathering brings together governments and civil society and takes place in New York City, where the United Nations headquarters are located.

This year, CSW67 convened organizations from different parts of the world but continued to carry many contradictions and power imbalances present on its global stage. Being held in the United States, the CSW brings together those who manage to obtain a visa and navigate the strict entry policies of the US, as well as access the funding necessary to join the discussions and participate in person. This affects many under-resourced collectives in the Larger World, especially those that suffer the harshest consequences of multiple/intersecting systems of oppression and injustice.

But what and how do feminist tech activists contribute to this year’s priority theme “innovation and technological change”? Digital technology has become a critical but often invisible infrastructure central to how feminist movements organize, protest, and engage in activism for structural and systemic transformation. Yet, technologies can also uphold, reproduce or worsen inequalities and forms of violence that affect women and LGBTQI+ communities. Feminist perspectives propose alternatives that question power relations and economies and create space for transformative changes in person and on the ground.

How can we build a feminist, decolonized internet and create technologies centered on anti-colonial, feminist values and practices? During the NGO CSW Forum, Whose Knowledge?, Numun Fund and APC (Association for Progressive Communications) co-held a parallel event on “Protest+Power: Feminist movement organizing in technology”, with grassroots activists coming from South America, Southeast Asia, and Africa. We invite you to learn more from their experiences at the forefront of feminist tech.

Feminist technology through the voices of four activists

The parallel event took place in the afternoon of March 10th, Friday, with dozens of attendees at the Church Center of the United Nations. With the moderation of Sheena Magenya, from APC, the conversation started with a brief introduction to the landscape of feminist tech in the Larger World. Jac sm Kee, co-founder and cartographer of the Numun Fund, kicked off the discussion with key data points on who funds and controls our network infrastructures and the platforms where we organize. She posed some of the questions that would permeate the whole discussion: what if technology was designed for and by the hands of the majority? What if it was shaped and imagined by feminist leadership?

Marla, from MariaLab in Brazil, explained how the collective thinks of and engages with feminist infrastructures: an open concept that is in development. To explore it, their methodology is centered in gender, with care (or “afeto”) at the core of its practices. Marla points out that MariaLab doesn’t believe that “technology will solve all problems”, but needs to question the terms under which this engagement happens.

As noted by speakers, inhabiting the digital space goes beyond a matter of access, and into questions about what you’re able to access and under what conditions. Irene Mwendwa, who works as Director of Strategic Initiatives at Pollicy, an Uganda-based organization at the intersection of data, technology, and design, highlighted the experiences of African women online.

![Irene Mwendwa, wearing a yellow jersey on the left, with text on the right saying: "The abuse and gendered misinformation that [come] in the way of African women leaders [are] beyond imagination. Because of these experiences, women leaders self-censor and reduce their participation in digital governance frameworks. This leads to digital policies not being gendered, such as data protection acts and social media tax laws."](https://whoseknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Irene.webp)

As summarized by Sheena Magenya, the imagined binaries between the oppressions of offline and online bodies are a lie. “The same oppressions that exist in my physical body, exist in my digital body.” Dhyta Caturani, from Purple Code, an intersectional feminist collective focusing on gender, human rights, and tech, recalled her experience as an activist in the early 2010s facing online abuse. But as she stresses in her interventions, the internet is “not a tool, it is a space where we live. We live our daily lives, we work, we do our activism, parallel to the physical space.”

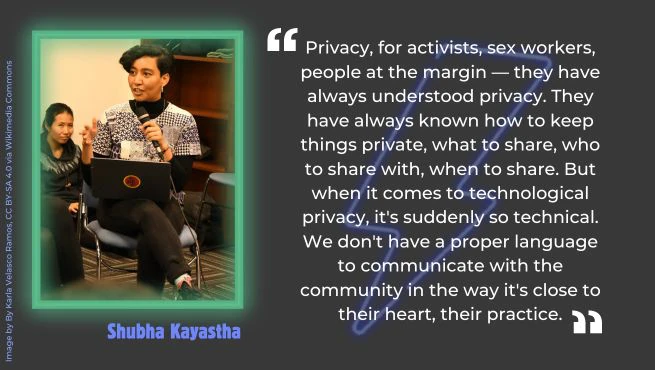

Shubha Kayastha, co-founder and Executive Director of Body & Data, a Nepal-based digital rights organization, notes that we still need to bring the language used to talk about these issues closer to communities. Oftentimes, including in public fora, like the United Nations, discussions frame technology as hard to reach, or only accessible to those who have gone through specific types of training. But women and marginalized groups always had to be innovative to survive, and tech is closer to them than these spaces might assume.

As highlighted by Sheena in her closing remarks as a moderator, “we’re not here to survive the internet,” but rather we’re here to be our full selves with our full rights as we exist in this world, both online and offline. With feminist tech that works for autonomy and freedom, we question the historical and ongoing structures of power and privilege — racism, colonialism, patriarchy, and other systems of oppression — and transgress their control over us. “That transgression is power,” summarizes Jac sm Kee.